An earlier version of this article about addressing big behaviors at school was published in the Attachment & Trauma Network’s December (2015) Therapeutic Parenting Journal. Here’s an updated version.

Big behaviors at school—every school’s got ’em. Maybe you’ve learned about adverse childhood experiences or been told that healthy relationships matter. While this advice is a start, it’s certainly not enough to help you meet the complex needs of your learners who experience significant dysregulation. When youth are tearing up school spaces or shutting down and disengaging from school, you need a trauma-sensitive approach that helps everyone be safer so you can get back to teaching and learning. I can help! Not with sticker charts or any other approach rooted in behaviorism. Rather, trauma-sensitivity is science-based. Keep reading for three ways you can shift your practice away from behaviorism in your K-12 classroom.

Not a Sticker Chart for Two Reasons

Practices rooted in behaviorism aren’t just counterproductive to trauma-informed education, they can be harmful, traumatic, or re-traumatizing for youth who have already experienced overwhelming stress. Plus, they can be unhelpful for kids who haven’t experienced adversity too. Here are two reasons why.

First, a behavior modification approach that utilizes reward charts or systems only works if folks are choosing their actions. This includes Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports (PBIS) or Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA). Many youth who have experienced trauma (plus those who may be dysregulated for other reasons) often aren’t choosing their behaviors. It’s like promising a carrot or waving a stick at someone who is having a seizure so they’ll stop shaking and do their schoolwork. Not very effective, right? Educators need to address the underlying source of learner stress responses instead of focusing on managing the behaviors that come from them.

Next, let’s explore a deeper question. “Even if behaviorism could change behavior, is it best?” I have long argued that it’s not. Why? These approaches utilize the same mechanisms as trauma. Trauma controls or manipulates people and takes their power away. Rewards, punishments, and comments like, “I like how so-and-so is following the rules,” are also attempts to coerce or manipulate learners. Youth and adults don’t need more disempowering experiences. They benefit from empowering ones within safe, caring relationships. That’s why working collaboratively to increase student agency is critical in trauma-informed care. To get there, let’s explore how teaching with trauma-sensitivity is science—meaning brain science!

Trauma-Sensitivity and the Brain

Practices rooted in behaviorism aren't just counterproductive to trauma-informed education, they can be harmful, traumatic, or re-traumatizing for youth who have already experienced trauma. Plus, they can be unhelpful for kids who haven't experienced adversity too.

Ms. Jen Tweet

Trauma-sensitivity is key to addressing big behaviors at school because nervous system distress causes them. Youth (and adults) aren’t choosing their stress responses and often can’t control them either. That’s why giving punishments and withholding rewards for youth often deepens frustration, embarrassment, shame, hopelessness, disconnection, and patterns of revenge. For youth who have experienced trauma (or neurodiversity not caused by adversity), these patterns risk giving folks another experience of being stressed, misunderstood, blamed, or rejected within relationships.

Teaching and learning about the science of trauma-sensitivity is empowering. The goal is to help everyone become more aware of their stress responses. First, you’ll want to encourage folks to listen to their bodies as they make choices that honor their needs. Next, you can explore how to support others. This matters because both youth and adults often benefit from closeness instead of trying to get regulated on their own. Together, your group can learn how to show up, reach out, and respond sensitively to one another.

Lessons on trauma-sensitivity and the brain, especially when paired with sound relational practices are empowering to everyone—all while they support health and learning for your entire group!

Lessons on trauma-sensitivity and the brain, especially when paired with sound relational practices are empowering to everyone—all while they support health and learning for your entire group!

Ms. Jen Tweet

Three Practices for Every Trauma-Sensitive Educator

Let’s explore three practices every educator can take to ground your work in trauma-sensitivity and science—as part of Tier 1 instruction about the human brain and nervous system.

1. Teach The Hand Model of The Brain

Discover Dr. Daniel Siegel’s (2003, 2012, 2014) hand model of the brain and teach it to your students so they can learn about their own stress response systems. For kid-friendly language and ideas, watch the replay of my YouTube Live from January 10, 2025. You’ll get suggestions for teaching and incorporating this concept in your kindergarten thru grade twelve (and beyond) classroom. Importantly, don’t teach the hand model of the brain when learners are experiencing big distress or a shut down of energy. Instead, initiate it when they’re regulated and ready to learn. To observe the hand model of the brain in action with youth, you’re also welcome to check out Hansen Elementary’s “Mindfulness” video to explore how my past third graders applied their learnings!

2. Start a Brain Books Project

With elementary aged students, you can also introduce brain books. This project invites learners to create their own nonfiction book about their brain and nervous system. My blog post about brain books gives you everything you need to get started with this assignment, including a template you can download and directions for students too!

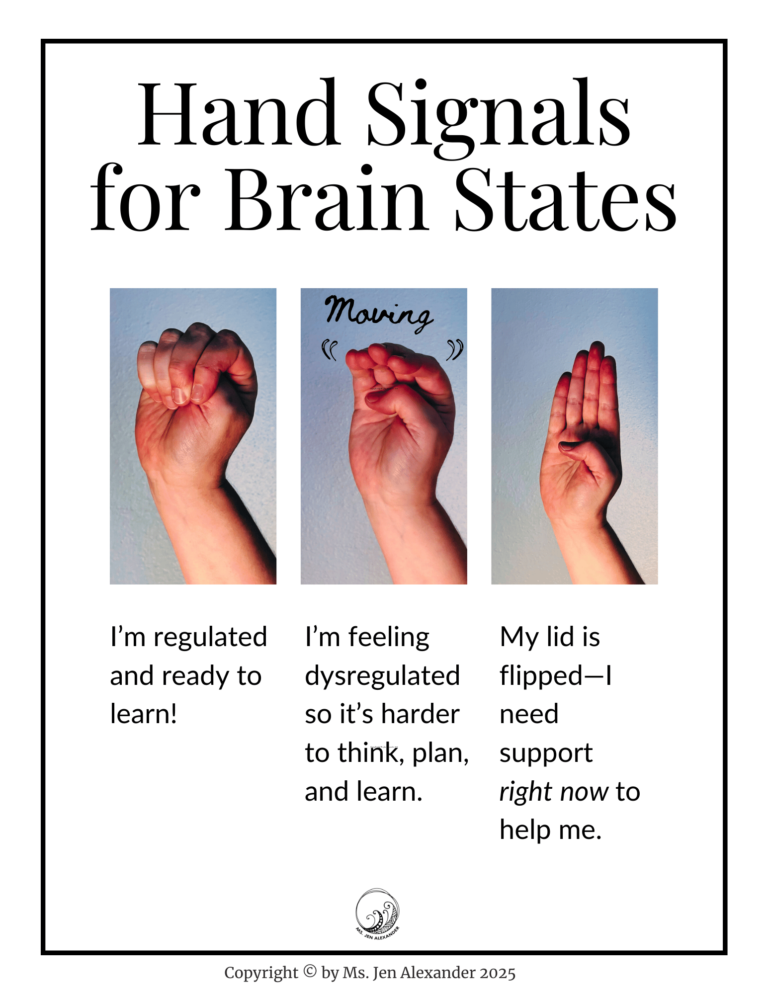

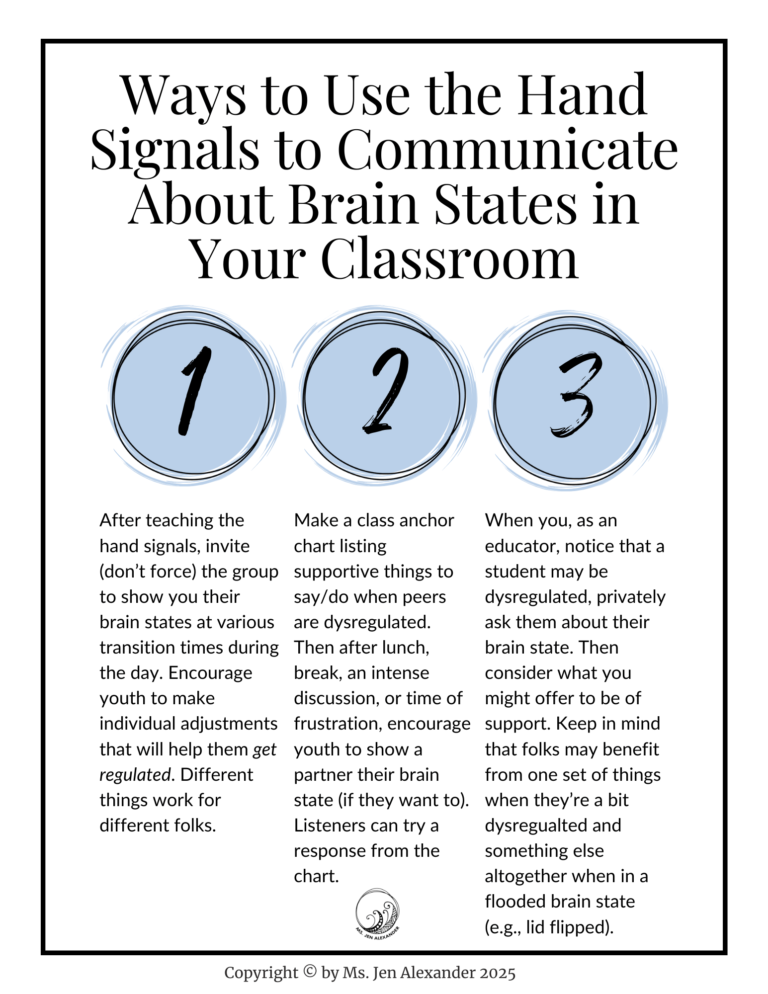

3. Use Hand Signals That Go With Brain States

With learners of all ages, incorporating use of hand signals that align with brain states is a practice that encourages getting regulated within relationships. Use this poster, which is also in the image below, to teach youth what each hand signal means. Then, when a learner signals dsyregulation, try communicating, “I can tell you’re stirred up (or shut down), let’s figure it out together.” This may help prevent further escalation. There are more ideas for use of these signals in your classroom on the second poster page!

While some students may need more than this instruction alone, ensuring every learner understands the neuroscience that goes with their feelings is an important first step. It’s why these core practices support regulation for all youth. Plus, you can build from them with Tier 2 and Tier 3 interventions as described in Building Trauma-Sensitive Schools.

With learners of all ages, incorporating use of hand signals that align with brain states is an important way to encourage getting regulated within relationships in the classroom.

Ms. Jen Tweet

To Learn More...

- Check out the Alliance Against Seclusion and Restraint’s explanation about why behaviorism is problematic in schools.

- Listen to my interview on the #TIENetworkPodcast. In it, I describe how to help a student get regulated. It’s episode 11, and you can find it on iTunes, Google Play, Spotify, or SoundCloud.

- Invite me to facilitate a keynote presentation for your group or sign-up for a free conversation to discuss training options. I promise that you won’t receive an introductory Trauma 101 seminar (unless you request that). Instead, your educators will learn what they can do within their unique roles to address big behaviors at school utilizing a trauma-informed approach. My publisher’s website is a great place to explore my offerings.

Helping you help kids,

References

Siegel, D. J. (2003). An interpersonal neurobiology of psychotherapy: The developing mind and the resolution of trauma. In M. F. Solomon & D. J. Siegel (Eds.), Healing trauma: Attachment, mind, body, and brain (pp. 1–56). New York, NY: Norton.

Siegel, D. J., & Bryson, T. P. (2012). The whole-brain child: 12 revolutionary strategies to nurture your child’s developing mind. New York, NY: Bantam.

Siegel, D. (2014). No-drama discipline: The whole-brain way to calm the chaos and nurture your child’s developing mind. New York, NY: Bantam Books.