My early parenting years inspired this piece. As a new mom to a six-year-old, I never rocked my girl to sleep as an infant or toddler. When she moved in, we had no established bedtime rhythm together, and nights were not easy for either one of us. If you’ve ever cared for a little one who fights sleep for any reason or wakes with nightmares and becomes distressed at the first signs of darkness closing in, you may know (like I learned) that there is no punishing or rewarding anyone into a sleep state. Instead, you figure out (as if your life depends on it sometimes) that comfort, connection, and consistency are what help most. In this piece, I propose that comfort and connection woven into consistent rhythms are also what schools need most right now to address out of control behavior.

Educators are expressing overwhelm about student behaviors being out of control as the stress of pandemic schooling continues. I’ll give you trauma-sensitive suggestions for addressing these problems. In short, they aren’t big changes but a focus on small ones instead.

Stress that is too much, meaning trauma, often leaves folks feeling out of control. That’s true if the events themselves infringe on one’s choices. It can relate to folks’ reactions making them feel powerless inside too.

COVID-19 itself has overwhelmed the world with one unpredictable wave of change after another. Many other layers of stress continue as well. We need collective efforts to solve the myriad of difficulties people are facing, yet communities (and personal relationships) are fractured, which makes next steps challenging.

In response to these conditions, the body’s energy goes up for some people while for others, it goes down. Also, distress goes out for some individuals and in for others. It might fluctuate between up or down as well as in and out too. No matter what, it’s affecting both educators and students. While we must do the deeper work to change what’s causing harm, personal comforts and small steps may help most now.

Educators May Feel Out of Control

While educators are doing their best to create some sense of normalcy at school (when things aren’t at all normal), difficulties abound. Staff shortages bring the need to cover for colleagues. Also, changes in expectations continue as the virus changes, which burdens faculty more than ever before. Criticism and hostility toward school staff have also been rising, contributing to a lack of safety and support. Furthermore, pressure to make up for all the losses since spring of 2019 understandably creates more burdens on humans who are trying their best to take good care of others when they and their own loved ones may be worried, ill, or grieving.

As folks crave normalcy and feel distressed without it, some educators may act as if things are normal. Others recognize that nothing is normal and carry the weight of that truth.

When adults are as overwhelmed (or shut down) as many are, the first priority must be to lessen stress wherever possible. Leaders must listen to and ease educator burdens whenever they can. Take anything off the plates that can go. Additionally, everyone should acknowledge the load that administrators are carrying too. It’s a lot for everyone.

Students Don’t Feel in Control Either

Obviously, not all stressors can be eased. As a result, expect youth to be affected by adult stress responses because caregiver stress impacts kids. That’s in addition to how the world’s big changes are impacting children and teens directly (e.g., by way of stress or loss related to threats and harm, family hardships, alterations to routines at home or school, less freedom and barriers to socializing, and high conflict between adults).

As social beings who need healthy attachments, being interdependent means good stuff or hard things within relationships impact everyone who is connected. Whether helpful or unhelpful, it’s the ripple effect. When it’s stress on top of stress, children and teens feel out of control inside too. Like the adults who care for them, they aren’t choosing these changes or the overwhelm they bring. They alone can’t soothe the tensions within their relationships either (though they may try to).

This doesn’t make it adults’ fault that students are feeling out of control. Rather, expect youth distress when relationships and the world are full of uncertainty and threat.

What Humans Do When We Don’t Feel in Control

There’s something everyone needs to understand about what tends to happen when humans feel out of control. We all seek control when we don’t feel in control. This isn’t necessarily a conscious choice. It’s just what happens.

“We all seek control when we don’t feel in control.”

It’s true of a toddler who melts down when they want to put on their shoes themselves but struggle. It’s also what might happen when a little one soaks up their caregiver’s distress after a family member dies and says “No” more often than usual.

For school age children, navigating the tensions and stress of the school day may result in increased irritability and tuning out of directions about chores at home. Or, when a family is understandably stressed by financial concerns caused by society’s inequities, a child may seek control by overpowering friends or not doing homework. It’s something they can control when there’s so much they can’t. Again, it’s not a conscious choice. It’s a response to feeling big stress.

Teens who are experiencing hostility between adults who fight about masks or whether to allow teaching about racism in schools may mirror that distress through their own peer group behaviors by joining in on challenges for vandalism (or something else). For those who are also experiencing racism at school or maltreatment in any setting, youth internal responses are likely even more overwhelming. Some will act out through aggression. Others may turn their distress inward, perhaps controlling their calorie intake or using substances to numb their feelings.

Of course, these are just a few examples of stressors and the reactions to feeling out of control that may accompany them.

Seeking Control Can Turn Into a Spiral of Doom

Educators who already feel out of control will understandably feel even more out of control when student behaviors escalate. As such, they may dysregulate more than they typically have in the past, resulting in more punitive words or actions. In turn, this causes kids to feel more distressed and out of control.

As both educators and students feel more out of control, they may become more controlling, activating the stress responses of the other. This creates what I often call “the spiral of doom.” Think increasing distress and hostility in the relationship(s) and more dysregulation for everyone involved.

The spiral of doom can happen in caregiver and youth relationships outside of a global pandemic. So, it shouldn’t shock us if it’s on the rise now when collective big stress is going into yet another year.

Importantly, if we don’t intentionally interrupt these power struggles, we risk untethering from one another at a time when we need each other more than ever. Stopping the spirals of doom, then, must be a priority.

Trauma-Sensitive Suggestions to Stop the Spiral of Doom

Unfortunately, there are no quick fixes. If there were (as I’ve said before) good educators would have landed on them by now. Here are four steps, though, that I encourage you to explore.

1. Recognize the spiral of doom and take the lead in slowing things down.

When a conflict between you as the educator and a student is escalating, try saying something like, “We all seek control when we don’t feel in control. I’m stressed and feel too little control. Do you feel like that too? When you’re ready please tell me about that experience if you want to. I’d like to try to understand before we make any decisions about what’s happening next. Then, when we do move towards trying to figure this out, let’s make decisions together so we both feel at least some control.”

Obviously, the spiral of doom is not reserved for 1:1 situations, particularly at school. Try words like these when a group is escalating. “We all seek control when we don’t feel in control. Let’s take a few moments to get regulated. I’ll play some music to help us. Then, when we’re all feeling at least a little better, let’s take turns sharing what’s going on for us so we can work together to help everyone feel more in control, instead of less.”

It’s also okay to say, “Whoa, this feels like a tug-of-war, I want it my way. Maybe you want it your way. I don’t like how I’m handling my stress responses right now. Let’s take a break. Then, I’d appreciate a do-over. Our relationship(s) matter(s) more than trying to win what feels more and more like a power struggle here.”

2. Listen to one another and to yourself; then center comfort.

Consider words like, “Let’s hear each other out without interrupting. Then, we can work together to find a solution that helps everyone get at least a little bit of what they need. Please start your sharing with phrases like, ‘I feel…’ and ‘I need…’ Then, listen while others are sharing instead of thinking about what you’re going to say next. It will be better to get through this together.”

Recognize, though, that when stress drives dysregulation, trying to solve every concern isn’t realistic or even helpful. Instead, say, “I’m hearing that we’re all stressed and it makes us irritable with one another. Let’s help ourselves by tuning into all things comforting.”

In Cozy: The Art of Arranging Yourself in the World, Isabel Gillies (2019) wrote that knowing ourselves is at the heart of coziness. Identifying things we are drawn to and who we connect with most can ground us and help us feel better. This explains why I love the feeling of turning on my bedside lamp—it goes with reading in bed. It’s also the reason I often appreciated sorting my daughter’s socks in her childhood. They were soft to touch and reminded me of how little and vulnerable she was. As Gillies explained, “Coziness is not about lying around. It’s the opposite. It’s the fuel you need to engage” (p. 191). Often, it comes from small comforts.

Similarly, Dr. Nim Tottenham (2021) presented research showing that items from our own early childhood can soothe stress responses even if that childhood included marked adversity. Maybe that’s why I loved tuning into episodes of Reading Rainbow when I babysat as a teen or young adult. It’s also why I’m drawn to Strawberry Shortcake stickers and other 80’s memorabilia.

More recently, small comforts in my daily rhythm like pouring water from an old brown pitcher into my essential oil diffuser each morning kept me going through long periods of really hard times. I couldn’t stop the harm from unfolding, but I could tend to myself and others around me. These choices gave me control while supporting rhythms sensitive to my personal preferences. Small comforts can help you and your students feel safe, be connected, and get regulated too. In fact, often, it’s the small things that get us through the really hard things in life.

"Often, it's the small things that get us through the really hard things in life."

3. Use what you learn in these dialogues and the above activity to consider how to collaboratively prevent future dysregulation instead of focusing on how you will punish students for problems if they occur.

Prevention always works better than punishment even if it doesn’t prevent everything, every time. It also conserves energy and can become part of a safe, connected, regulated rhythm in your class or school. Often, I think of these rhythms as a way to nurture high expectations rather than control for them. Remember, we can’t punish anyone out of a trauma response. And, people in distress need agency.

"Prevention always works better than punishment even if it doesn't prevent everything, every time."

Here’s one way to approach this.

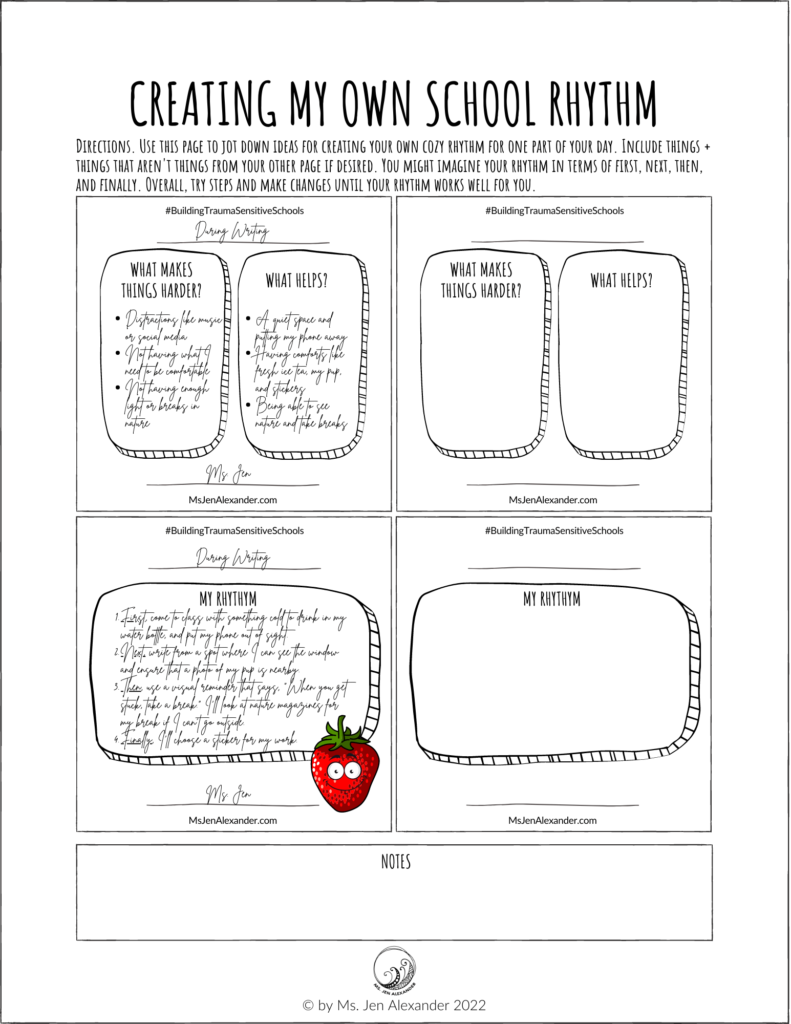

Start by noticing times in your schedule when dysregulation tends to go up, then invite students to design their own personal rhythm for that part of the day. Assist as needed.

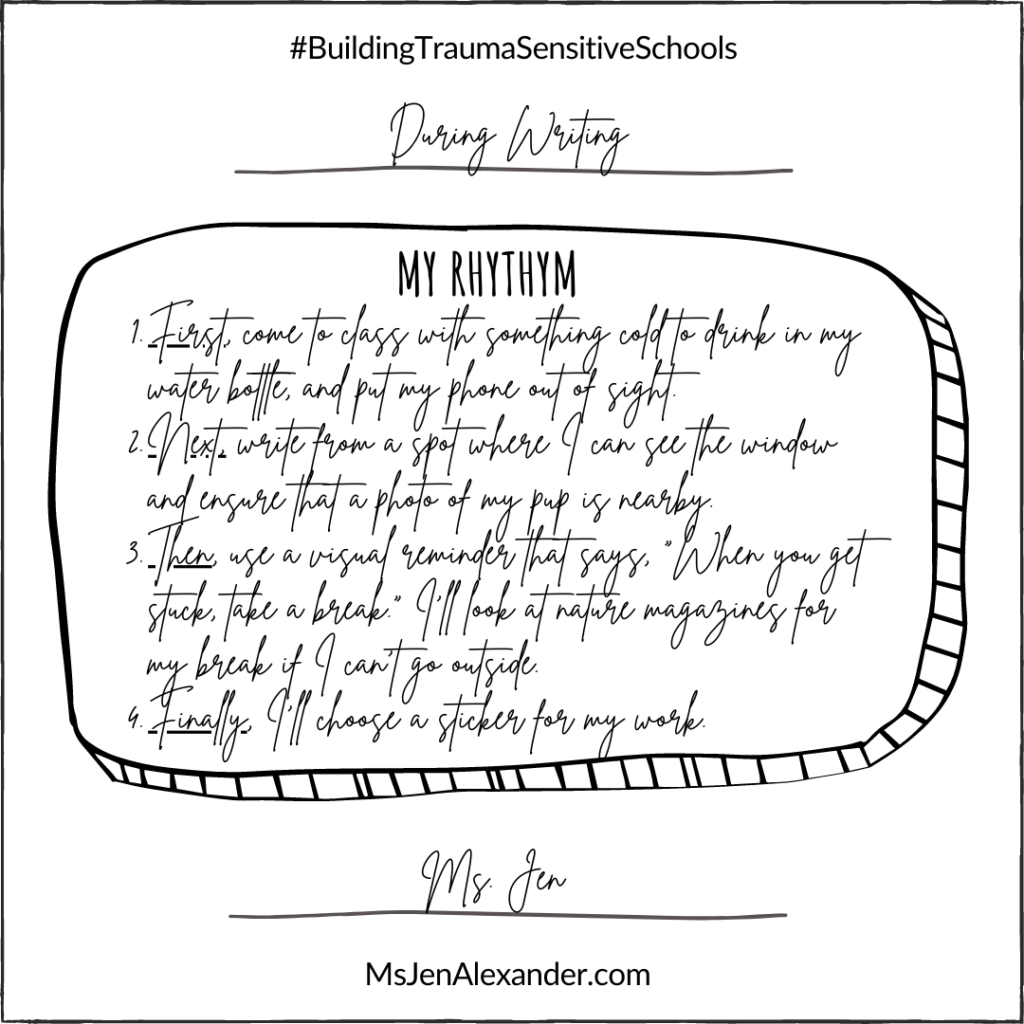

For instance, if writing seems to be more difficult than other times, invite each student to experiment with and create their own rhythm for that block to bring choice and predictability as well as regulation for themselves as individuals.

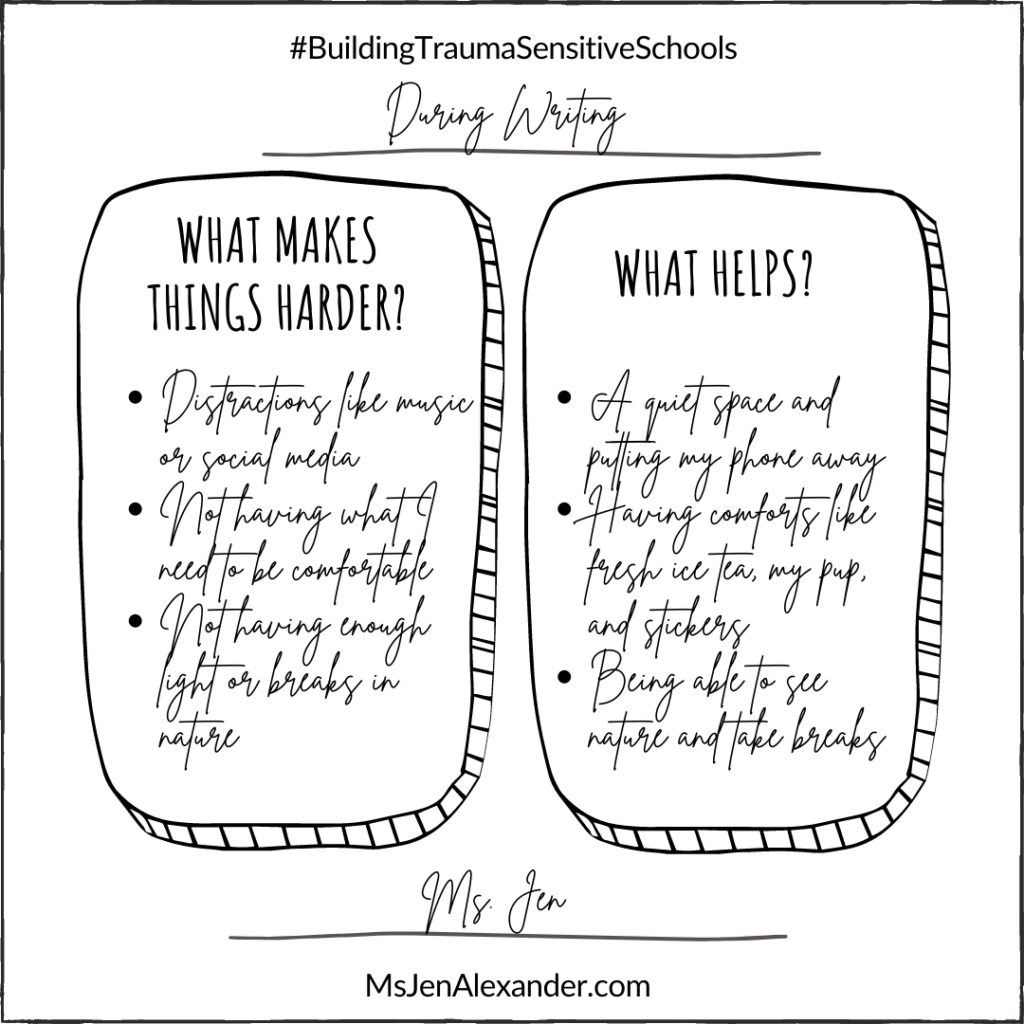

To accomplish this, explain how each person should make two lists. 1)Things that make things harder for them during the identified time and 2) things that help.

When I write, for example, distractions like music or social media make things harder for me. It helps when I can get settled and have comforts to help me keep going so I don’t interrupt myself. As such, I’ve found that taking the time to brew tea and then, put it on ice so I have something cold and tasty to drink while I write helps me. I also do better when I’m near my pup, sunlight, or can take breaks in nature. Overall, though, I tend to need reminders to take a break when I get stuck.

What might this like at school step-by-step? I cannot necessarily brew tea in that space so it’s important to consider how to design my own rhythm creatively. For starters, I could put my phone out of sight and settle in a spot where I can look out the window. I might also put ice tea in my water bottle before class and take several mindful sips before writing. Additionally, I would benefit from putting a sticky note nearby that says, “When you get stuck, take a break.” To do that, I could ask for (or arrange to have) magazines with nature photos in the classroom that I could look at. Or, I could plan to tend to a class plant each day during a writing break instead. Finally, I enjoy stickers, especially vintage ones so I would choose a real or virtual one for my own work!

Thinking through what makes things harder and what helps can support everyone in designing their own rhythms that allow them to do their best every day, including times when they’re more distressed. The familiarity and predictability of these patterns can comfort and carry folks through difficult times by soothing stress responses. When everyone does this in their own way, it can create a more regulating classroom for everyone. Use the worksheet below as part of a lesson to help students create their own school rhythm.

Importantly, don’t forget to take time to reflect on what’s working in these rhythms and how they may need to change over time. Often, individuals need to try things to see what works and doesn’t work, adjusting as they go. Use the notes section for this if desired.

Will this kind of individual planning take time and flexibility? Yes, and it’s worth it if it promotes a sense of agency over one’s school rhythms, supports safety and regulation, and helps everyone learn.

4. Think about how to infuse other opportunities for choice throughout everything you do.

While creating a personalized rhythm for every part of the school day may be too much, especially all at once, you can infuse more choices for students throughout the full daily schedule.

Consider how you might add in choices in other parts of your regular routine wherever you can.

Here are a couple of examples.

Instead of having one attendance (or transition) question, for instance, offer different options so students can choose which one to answer. I’ll list a few of my current favs below, which are organized in terms of people, places, and things.

- Name a book character you wish you could be friends with. Or, name a character you’d more likely consider an enemy.

- Share about a place that means something to you. Or, one that bores you.

- What dessert might you order? Or, what dessert would you never order?

Instead of three math problems as part of a review at the start of class, present six and invite students to do either the evens or the odds. Or, celebrate something by inviting students to brainstorm various board games they could set up to play in the classroom.

Choices—find them, create them, and embed them!

Better yet? Initiate a mini-lesson where you teach students how stress impacts regulation, causing us to seek control when we don’t feel in control. Ask them about times when they’ve noticed this response in folks (or in themselves). And, discuss what helps too. Then, lead a class discussion about student ideas regarding where more choices could be emphasized throughout the school day.

Navigating ongoing trauma often necessitates that we focus on life one step at a time. Sometimes it means we consider how to get through this moment, then the next one. Being intentional with these choices can increase personal agency, predictability, and success at school. It can help interrupt the spiral of doom too. Above all, it centers comfort and taking good care, which influences regulation.

To Learn More…

Schedule a 20-minute consultation with Ms. Jen to learn how you can bring a less than 1-hour virtual training to your staff that will help them help kids right now when behavior problems are of concern. Feel free to download the flyer below as well. Other options are available for tailoring other seminars for your teams too.

I see you,

#BuildingTraumaSensitiveSchools #NoticeTheNeed #MeetTheNeed #FeelSafe #BeConnected #GetRegulated #Learn #FeelingDealingAndHealing #TakeGoodCare

References

Gillies, I. (2019). Cozy: The art of arranging yourself in the world. New York, NY: Harper Collins Books.

Tottenham, N. (2021, September 30). The development of emotion regulation neurobiology and the role of experiences [Conference presentation]. 2021 ATTACh Annual Conference, Minneapolis, MN, United States.w