Once a therapist said to me, “Self-love may be too hard; aim for self-compassion.” Self-compassion, though, can be difficult too. What gets in the way? Would clearly defining compassion and self-compassion help? And, how can educators deepen their compassionate practices by listening to their bodies, particularly when nearing the end of an incredibly stressful school year? Let’s explore each of these questions in more depth.

Individuals Get in Their Own Way

I have certainly gotten in my own way when it comes to practicing self-compassion. Maybe you have too.

Both professionally and personally, I’ve experienced too much stress on repeat over the years. Historically, my default when things have been at their worst was to executive function my life like nobody’s business until I just couldn’t anymore because my body wouldn’t let me. Often, I thought, “If I could just get this or that accomplished, things will be better.” When that became overwhelming, I’d be quite hard on myself—even harsh at times. Eventually, I might promise myself a reprieve later with words like, “I’m going to push through these next dozen things plus the set after that. Then, I’ll rest.” Increasingly, however, I often concluded there wasn’t time to rest. Or, if I tried to do so, it sometimes felt nearly impossible to relax, even on breaks.

I know I’m not alone in these struggles, especially in the field of education—a profession that means much and can demand more than faculty have to give when it comes to just about everything. Patterns like these can also be linked to childhood experiences as well as socio-cultural norms, particularly those rooted in whiteness and Western-dominated societies. Educators may push themselves too much, feeling justified at best (and superior at worst) because after all, it’s “for the kids.” Any approach like this lacks self-compassion, though, and is terribly unhealthy for adults and youth.

Systems as Barriers to Self-Compassion

Systems, of course, can also get in the way of how we tend to self and one another compassionately.

As stated by Laura van Dernoot Lipsky with Connie Burk (2009) in Trauma Stewardship, “Every larger system has an obligation to the people who make it work, as well as to the people it serves” (p. 17). Too often, however, folks are pushed to find a compromise between what they can do and what they’re charged with doing, which can lead to ethical and moral dilemmas. What follows is a reaction to too much stress, which may include resignation to the status quo through comments like, “The system is broken.” Or, “This is just how things are so we have to make the best of it.” These stances, however, help things remain exactly as they are, which perpetuates systems that take advantage of, abuse, and oppress people.

We must have conversations about how we came into our work, the ways it affects us, and how we make meaning out of our experiences so we can learn from them (Lipsky, 2009). As educators, students are entrusted in our care. Part of honoring youth means honoring the staff members and families who care for them.

Taking Good Care to Improve Compassion

How do we change un-compassionate patterns that don’t always take good care of people? Meaning, how can individuals honor their own feelings and needs as well as those of colleagues? Importantly, how do we get teams, schools, districts, communities, states, and nations to truly honor educators too? Not through lone acts like placing pop-up signs of thanks in employees’ yards (if they even have a yard) but rather, through genuine change, support, appropriate allocation of resources (including human ones), and compassionate care when individuals or groups are vulnerable and hurting. Collectively, we must consider what taking good care of one another really means when educators are experiencing trauma themselves, whether during a pandemic or not and in relation to school or outside of it. It all matters. Adults who can show up for themselves and one another will find it easier to genuinely show up for kids, especially long term.

Adults who can show up for themselves and one another will find it easier to genuinely show up for kids, especially long term.

Defining Compassion and Self-Compassion

I have many ideas about how we can engage in this deep work together, and I don’t have all the answers by myself.

Perhaps one place we can start is by defining compassion and self-compassion. Dan Siegel (2015) explained that compassion is “feeling with another person.” Self-compassion then, would be feeling with oneself. Compassion overall means being present to self, others, and the world—not as robots who are shut down and feeling not enough, nor as folks who are reacting too much—both of which can be responses to stress. It requires the capacity to feel just right in a regulated, receptive (rather than reactive) state so that we can take action to alleviate suffering and do our part to help everyone flourish. Similarly, Tara Brach (2019) has taught that compassion, including her work on radical compassion, is a way to heal. All of these ideas are rooted in the wisdom of Indigenous peoples who have long understood the power of community in helping folks transcend their suffering (Katz, 2017).

When it comes to self-compassion, Kristin Neff (2013) detailed three necessary components. These include 1) treating ourselves gently instead of harshly, 2) finding common humanity, and 3) being with what is in the present moment through mindfulness. In short, we have to acknowledge the truth of suffering in self and others before we can offer compassion.

Tips for Self-Compassion as the School Year Ends

This pandemic school year and the time preceding it have taken a toll on many educators. If you are one of them, please recognize that self-compassion and compassion in your community are integral to healing. You can’t heal what you don’t feel so start there. Show up for yourself. Be present. Stay still enough to notice the effects of your own suffering. You don’t have to change what you’re feeling, just acknowledge it. Then, lean into what your body needs when you’re ready.

You can’t heal what you don’t feel so start there.

For instance, are you feeling exhausted? Heavy even? And, depleted? Is your mind empty or full and scattered? Or, are you overwhelmed inside and very much needing everything to change or slow down? Is your heart racing? And, is your stomach in knots? Instead, maybe you’re simply hopeful about wrapping up the year; the effects of 2020 and 2021 may hit you later if your schedule frees up. Or, your experience may be entirely different from these descriptions.

No matter what, listening to your body from moment to moment is one way to practice self-compassion and thus, support your own recovery from this year’s (and previous years’) big stress. As I (2021) like to say, #NoticeTheNeed. Then, #MeetTheNeed. Here are a few examples.

- If your body is sending signals about needing rest, then rest.

- When everything feels too much, decrease sights, sounds, and all the things.

- Feeling cooped up inside? Get outside in nature if you can.

- If you feel like moving, stop what you’re doing and move in safe ways.

- When you’re hungry, eat. Thirsty? Drink.

- Do you need more space, light, beauty, and joy? Explore, find it, and create.

- If in need of peopling, people.

- When peopled out, pull back.

- Are infants, puppies, kitties, or baby goats calling your name? Seek them out.

- Perhaps music, writing, or reading (or something else entirely) sounds just right. If so, lean in, and pause when that feels best too.

Listening to your body is a way back to yourself. It’s the foundation of self-compassion. As such, it’s a way to trust and take good care of yourself. And, when everyone does that together, our communities can compassionately begin to heal too.

Listening to your body is a way back to yourself. It’s the foundation of self-compassion. As such, it’s a way to trust and take good care of yourself.

To Learn More…

- Read the blog post over at the Inclusion Lab by Brookes Publishing that features four trauma-informed tips for helping all students learn—all while the world opens up more in this phase of the pandemic.

- Explore Dr. Kristin Neff’s (2013) research about self-compassion by watching her TEDx presentation called The space between self-esteem and self compassion.

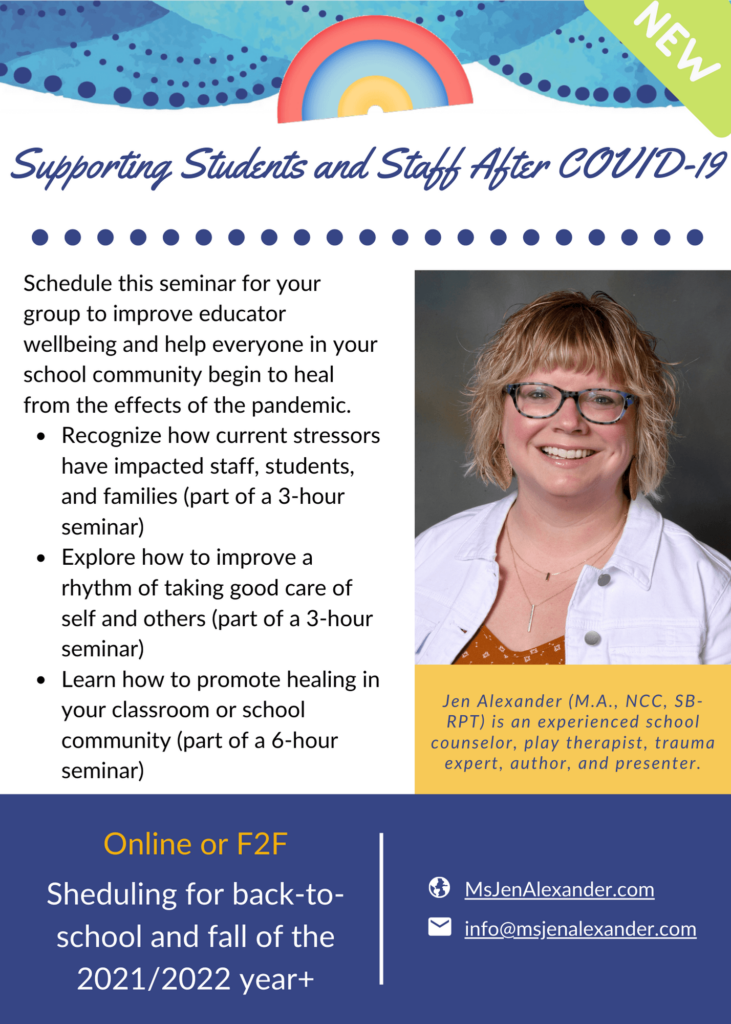

- Learn more examples of how to improve educator wellbeing and promote healing in my new book Supporting Students and Staff After COVID-19: Your Trauma-Sensitive Back-to-School Transition Plan.

- Check out my affirmation cards with beautiful watercolor backgrounds that can help you take good care of self and others. They’re available for purchase online in Ms. Jen’s Shop.

- Read Karen Ray Costa’s (2021) The next phase, which explains what a trauma-aware approach to the next phase of the pandemic could look like for higher educators.

- Learn more about how to support educator wellbeing at one of my upcoming trainings on my events and training opportunities page. Or, consider inviting me to facilitate a partial day or full day professional learning seminar for your staff either virtually or face-to-face. The flier pictured below outlines one popular option that administrators are currently scheduling for back-to-school inservice and fall PD in the 2021/2022 school year. Download the flier below if desired and email me at info@msjenalexander.com to learn more about how this seminar can support your teams.

There’s much we can do with one another to transcend all that has been and is continuing to happen in our communities. I’m here to partner with you in these critical efforts.

Take good care,

#BuildingTraumaSensitiveSchools #COVID-19 #CollectiveTrauma #Recovery #HopeAndHealing #HelpingYouHelpKids

References

Alexander, J. (2021). Supporting students and staff after COVID-19: Your trauma-sensitive back-to-school transition plan. Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co.

Brach, T. (2019). Radical compassion: Learning to love yourself and your world with the practice of RAIN. New York, NY: Viking.

Katz, D. (2017). Indigenous healing psychology: Honoring the wisdom of the first peoples. Rochester, VT: Healing Arts Press.

Neff, K. (2013). The space between self-esteem and self compassion [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IvtZBUSplr4

Siegel, D. (2015). Interpersonal neurobiology: Why compassion is necessary for humanity [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QWE0VAzpxxg

van Dernoot Lipsky, L. & Burk, C. (2009). Trauma stewardship: An everyday guide to caring for self while caring for others. Oakland, CA: Berrett-Koehler Publishers.